Beyond Elimination and Construction: Zen, Symbolism, and the Perennialist School[1]Co-first authorship statement: both authors contributed equally to this work. The paper is a result of the work within the research program “Philosophical Investigations” (P6-0252), financed by … Continue reading

This paper was first published in Ars & Humanitas, 16(2), pp. 165–178. https://doi.org/10.4312/ars.16.2.165-178

Keywords: Zen, enlightenment, perennialism, constructivism, symbolism, transcendence

As Zen took root in the West over the past century, there emerged a number of differing interpretations of one of its key facets, namely the question of the relationship between language and enlightenment. The two camps which came to garner the most attention in philosophical circles are eliminativism, which understands enlightenment as the cutting off of linguistic and socio-cultural categories, accomplished by arbitrary means, and constructivism, which identifies satori with the exercise of certain linguistic and cultural conventions. In the present paper, we first lay out some of the most important criticisms of these two positions, arguing that the two accounts fall into the error of either demonizing or fetishizing language, respectively, before outlining a different approach to the relationship between practice and realization, drawing on the largely neglected work of perennialist thinkers and a phenomenologically informed notion of symbolism. By taking the idea of the symbol in its double meaning, namely as that which “casts together” the culturally conditioned particularities of Zen into a unified tradition, and yet points beyond them as a “sign” of something that itself transcends all description, we propose an interpretation that can do justice both to the crucial role played by concrete practices and to the transcendent nature of their soteriological “end.”

1 Introduction

The Bhagavan has said,

“From the night I attained perfect enlightenment

Until the night I enter nirvana, between the two,

I do not speak, nor have I spoken, nor will I speak a single word,

for not speaking is how a buddha speaks [不說是佛說].”

(Laṅkāvatārasūtra, T.16.670.0498c17; Pine, 2012, 175)[2]We will be referencing Red Pine’s translation of the Laṅkāvatārasūtra throughout; a reference to Guṇabhadra’s Chinese text from the Taishō Tripiṭaka will also be given, but the volume … Continue reading

In this paper, we tackle a highly contentious issue in Zen, namely the relationship between enlightenment, understood as satori or “seeing one’s nature” (Bodhidharma, 1989, 11), on the one hand, and the linguistic and socio-cultural means that constitute the path that leads to enlightenment on the other. More specifically, we outline a novel answer to the question of whether (and, if so, in what way) enlightenment is transcendent in relation to the path leading to it. This question is not merely an exegetical one, but has important consequences for our understanding of the nature of Zen Buddhism, for if enlightenment is completely dependent on particular socio-cultural conditions – for instance those that form the milieu of a typical Zen monastery – then there can be nothing universal about it (i.e., it becomes impossible to speak of a “trans-confessional core” in Zen). This latter issue itself, namely that of universalism, is, of course, beyond the scope of the present discussion.[3]See Vörös, 2013, 23–102. The question is rather whether such an interpretation of Zen is possible given the role that is played by concrete (linguistic and non-linguistic) practices.

In the first two sections, we will present an (apparent) dichotomy between two radically different ways of approaching this question: the (phenomenologically) eliminativist view, which understands enlightenment as pure experience radically independent of social and linguistic conditioning, i.e., a radical elimination of conceptuality, and the constructivist view, which takes satori – along with all other aspects of the Zen Path – to be “a uniqueand impressive cultural achievement particular to East Asian societies” (Wright, 1992, 117, our emphasis). Finally, in the third and fourth sections, we will present some of the key difficulties inherent in these two accounts and attempt to sketch out a different understanding of enlightenment, a via media between the Scylla of unconditioned experience and the Charybdis of culturally determined practice, drawing on the notion of symbolism as it was developed by thinkers in the perennialist school (R. Guénon, F. Schuon and A.K. Coomaraswamy).

2 Dropping off body and (discursive) mind?

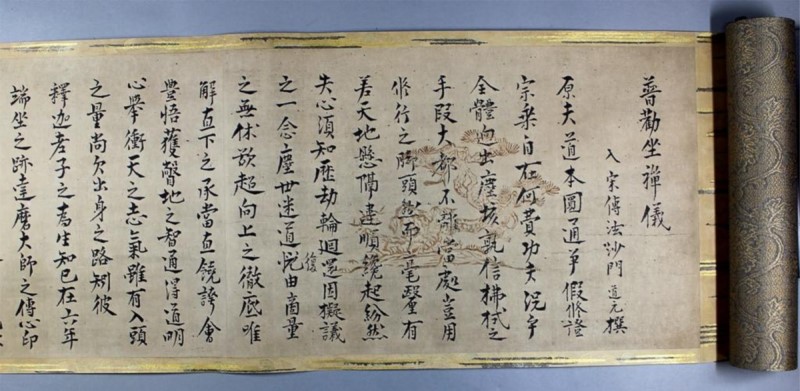

Although the eliminativist view that will be discussed here emerged in the 20th century, it also finds support in some of the foundational texts of Zen. To illustrate this, let us look at two classical examples that are often cited in support of the eliminativist interpretation. In a famous declaration, most likely from the early Tang Dynasty, Zen is characterised as “a special transmission outside the scripture […], not depending upon the letter, but pointing directly to one’s Mind” (Suzuki, 1938, 48). Similarly, in Bodhidharma’s Bloodstream Sermon, we read:

Even if you explain thousands of sutras and shastras, unless you see your own nature yours is the teaching of a mortal, not a buddha. The true Way is sublime. It can’t be expressed in language. Of what use are scriptures? But someone who sees his own nature finds the Way, even if he can’t read a word. Someone who sees his nature is a buddha. And […] a buddha can’t be found in words or anywhere in the Twelvefold Canon. (Bodhidharma, 1989, 29)

If these and similar admonitions to avoid “the nets and snares of words” are taken seriously (Dōgen, 2007a, 10), one is left with the impression that enlightenment entails eliminating discursivity so as to gain an immediate access to reality. Linguistic categories, as well as all other types of socio-cultural conditioning, would thus form a veil that must be removed if we are to see reality for what it is. This view was taken up by many early Western interpreters of Buddhism in general and Zen in particular, especially those in (psycho)therapeutical communities (see Harrington et al., 2013; Taylor, 2000). Erich Fromm, for instance, sees Zen satori as a breaking away, or ultimate liberation, from the various forms of enculturation, which, since they are the end result of the process of repression, restrict our everyday reality to only “those feelings that can pass through the social filter of language, logic and meaning” (Fromm et al., 1971, 162).

The eliminativist approach presupposes that conceptuality, often understood in a rather broad and loose sense, can be separated from a non-conceptual “core” of “pure experience”. In Fromm’s view, for instance, enlightenment is “the direct, non-reflective [unreflektiert] understanding of reality, without affective contamination or conceptual elaboration”, a kind of “repetition of the pre-intellectual, direct understanding of the child, but on a higher level” (ibid., 171). Clearly, the main emphasis here is on the removal or elimination of conceptuality, which seems to be but a restatement of the Zen emphasis on the famous “backward step”, or the turning of the mind inward, as famously expressed in Dōgen’s canonical text Fukanzazengi (Dōgen, 2007b, 363).[4]While Dōgen’s Sōtō school does differ from other Zen traditions in its concrete forms of practice (although the difference is primarily one of emphasis), we can still take it as representative … Continue reading

Despite its seemingly uncontroversial nature, this interpretation rests on a highly tenuous presupposition about the relationship between experience and conceptuality. As Wright points out, the eliminativist account takes for granted the so-called “instrumental theory of language” – “the belief that language is an avoidable and optional element in human experience” (Wright, 1992, 114). In other words, for Fromm and other eliminativists, human cognition is conceived of as a stratified or layered cognition, in which the layer of pure experience – pure observation, sensation, etc. – is, somehow, superimposed by the socio-culturally mediated conceptual structures. While these can be extremely useful from a pragmatic perspective, e.g., by helping us manoeuvre through the innumerable complexities of our natural and social surroundings, they are also existentially and ontologically misleading – and principally so – as they necessarily introduce simplifications, delimitations, and thus distortions into the unified meshwork of pristine, mute experience.

This stratified view of cognition, made popular by the empiricist tradition, has a certain intuitive appeal. On closer inspection, however, it proves to be philosophically suspect for at least three reasons. To begin with, it seems to introduce a yawning, perhaps even unbridgeable gap between the two cognitive layers: if perception and cognition, experience and conceptualization, are so disparate, it is difficult to see what ties them together. Secondly, and relatedly, the status of intellection – as an activity utilizing concepts, etc. – seems contingent and secondary, which is profoundly at odds with the prominence it plays in both our everyday and professional lives. Thirdly, and most importantly for our purposes, this conception seems to be unable to account for the transcendent nature of satori. That is, even if we accept, provisionally, the idea that satori is similar to, as Fromm puts it, “the pre-intellectual, direct understanding of the child”, how are we to explain the last part of Fromm’s statement: “[…] but on a higher level” (Fromm et al., 1971, 171). What higher level? Are we to posit yet another – third – level beyond the level of conceptualization? But if so, why call it pre-reflective? Surely, something is amiss here.

3 Enlightenment constructed?

This criticism of Fromm’s presuppositions regarding the relationship between conceptuality and experience has played an important role in later discussions. As Wright, a key figure in the debate, continues: “Feelings, like thoughts, are shaped and moulded by the language that we have (instrumentally) taken merely to ‘express’ them […], ‘cerebration’ and ‘affection’ are not independent domains that can be so easily juxtaposed” (Wright, 1992, 115). From his perspective, Fromm not only “eliminates what is valuable and interesting in cultural studies” but also “fails to understand Zen enlightenment as a unique and impressive cultural achievement particular to East Asian societies” (ibid., 117, our emphasis).

Wright’s alternative account starts from the notion that human perception is always shaped by linguistic categories, i.e., that there is, and can be, no “pre-linguistic, objective ‘given’” (ibid., 118). By highlighting the interdependence of perception, language, and thought, he thus arrives at a view diametrically opposed to that of Fromm. In a particularly telling passage, he writes: “Because he is a perfect instantiation of the cultural ideal, the Zen master can be understood to be ‘relatively more’ determined and shaped by the Zen community’s linguistically articulated image of excellence” (ibid., 123, our emphasis). Thus, what is at stake here is not the phenomenologico-hermeneutical thesis on the fundamental inseparability of language and perception, which Wright takes from a specific reading of Heidegger – this, after all, only concerns our ordinary, non-enlightened experience, and even Dōgen would be happy to concede that here we remain entangled in the “nets and snares of words” – but his extension of this view to both the pursuit of enlightenment and enlightenment itself. For Wright, then, neither is the Zen path a specific way of fulfilling a pre-existing motivation for spiritual realization (perhaps stemming from a kind of existential dismay or disillusionment inherent in the human condition, referred to in Sanskrit as saṃvega), nor is enlightenment a specific mode of its appeasement. Rather, both the pull towards and the very attainment of enlightenment are the result of a culturally specific framing, which functions primarily through the imitation of role models – Zen monks who embody specific social norms (ibid., 125). Enlightenment, then, is constructed all the way down.

Much could be said about the way Wright understands the concrete Zen practices in light of this interpretation (e.g., the surprising view that kōans merely serve to prove linguistic determinism (ibid., 127)), but for our purposes, the following points are of utmost importance: on his view, the aspiration and path towards, as well as the attainment of, enlightenment is: (1) linguistically and conceptually conditioned, hence (2) unique to a particular milieu, and (3) attainable only through a long process of training, where this training is taken to consist primarily in a kind of “linguistic shaping” (ibid., 131).

How does this view square with the textual sources? Zen texts are, as Wright himself agrees (ibid., 129), replete with references to enlightenment as transcending language; however, he is quick to add that these references function merely as ironic statements (insofar as they involve “speaking against speaking”) aimed primarily against reflection (as typified in more scholarly branches of the Buddhist tradition), rather than as explicit statements about enlightenment that should be taken at face value (ibid., 130). However, there is a curious paradox at work here. Namely, it would seem that the constructivist argument hinges on reinterpreting the textual sources in light of a particular (post)modern understanding of language so as to fit enlightenment into its own conceptual box, which is precisely the sort of hermeneutic transgression that Wright accuses Fromm of committing (see ibid., 115). But even more importantly, while this view rightly criticizes the naïve universalism of the eliminativist approach – the idea that individual linguistic and practical forms of any given tradition are just so many pragmatically useful, but ultimately arbitrary, ways of approaching the trans-cultural domain of pure experience – it does so only at the cost of permanently enclosing the Zen tradition within itself. In other words: if Zen is, in fact, determined by a particular language and culture, then what are we to we make of the flourishing of Zen in the West in recent decades (see e.g., van der Braak, 2020; Ford, 2006; Wallace, 2003)? Perhaps even more importantly, given that cultural and linguistic practices also change over much smaller temporal and geographical distances, is it even feasible to talk of a unified Zen tradition in China and Japan – or, for that matter, in a rural temple and a bustling head monastery in the same region?

If these questions never seem to appear as problems to Zen practitioners themselves, and if a deeper mutual understanding between Zen and other traditions, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist, is not only possible, but even seen by notable practitioners as fruitful (e.g., Suzuki, 2002), then this is because the concrete historical forms (doctrines, language, iconography, etc.) are never understood as being exhaustive of the dynamic essence of the tradition. This, moreover, is not a Western romantic and orientalist interpretation of Zen, but rather a view repeatedly stressed in Zen’s foundational scriptures. Thus, in the Laṅkāvatāra even the notions of existence and rebirth – two central pillars of Buddhist philosophy – are portrayed as skilful means, i.e., pragmatic tools whose only purpose is to lead the practitioner to the other shore (0494a10–23; Pine, 2012, 139–41). Once there, all teachings fall by the wayside, for language is of no help where subject and object no longer arise (0497b02; Pine, 2012, 163; Dōgen, 2007b, 5–6).

4 Practice and transcendence

It would seem, then, that our discussion has come full circle and we are ultimately forced to accept that, despite all its theoretical shortcomings, eliminativism is nevertheless correct. However, there are at least two good reasons why this conclusion might be premature. First, while it is true that eliminativism doesn’t present enlightenment as a linguistic and cultural construct (and hence attempts to keep enlightened experience outside of the realm of conceptual description), it is no less true that it remains committed to a very particular view of what enlightenment consists in, namely the elimination of conceptual elaboration of pre-reflective experience. This, however, is likewise contradicted by the foundational texts of Zen, for they are emphatic that nirvāṇa is “not the destruction of anything” (0504c05; Pine, 2012, 209; see also Dōgen, 2007b, 129).[5]Note that this denial applies especially to the destruction of mental faculties or “views” (見). In a different section of the Laṅkāvatāra, the view that nirvāṇa consists in the … Continue reading In this sense, Wright’s charge of imposing modern notions on an ancient tradition stillholds true for eliminativism (although arguably less so than for his own brand of constructivism): when interpretative push comes to hermeneutic shove, theoretical commitments are given priority over faithfulness to the tradition itself.

Secondly, and crucially, eliminativism can’t clarify the relationship between concrete practices and the “end” they lead to (taking the latter term in a very provisional sense). In other words: if enlightenment is merely the elimination of certain habitual mental tendencies, then there is no reason why the same goal couldn’t be accomplished, say, by the administration of psychoactive drugs or even direct brain stimulation (which helps explain why eliminativism has been so popular among scientists studying meditation). That is, the specifics of the path are, fundamentally, irrelevant. Thus, if constructivism ends up reducing the end to the means, eliminativism in turn reduces the means to a mere contingency, an inevitable nuisance.

What is needed, then, is a mental framework that would allow us to understand both the critical role played by socio-culturally conditioned practice, such that the relationship between practice and realization isn’t arbitrary, and the radically transcendent nature of realization itself. In what follows, we would like to tentatively explore one such framework, which so far has been unfortunately largely neglected in contemporary scholarship on Zen, as well as in contemporary philosophy of religion in general, namely the rich tradition of perennialism, as it was laid out in the works of René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, and others. While reasonably well-known in some fields of research, primarily that of Islamic philosophy (e.g., Nasr, 1989), perennialists remain little-known in Buddhist studies, with only a few notable exceptions (e.g., Suzuki, 2002, 9–10), despite the fact that some of the perennialists wrote extensively on Buddhism (e.g., Coomaraswamy, 1916; 2011; Schuon, 2018) and much more extensively on the Vedic tradition in the context of which Buddhism arose (e.g., Guénon, 2001a; 2001b; Schuon, 1959; Coomaraswamy, 1933).

Briefly put, the perennialists hold that while traditions differ in their exoteric aspect (which is said to include everything from language to concrete practices), they are ultimately unified in their esoteric aspect (Smith, 1984, xii). The latter refers to the apprehension of the Absolute,[6]This term is used very often in perennialist texts, but it doesn’t entail any sort of objectivization of metaphysical realization. What is in question here is beyond what can properly be subsumed … Continue reading a sphere that Guénon terms metaphysics. This concept can be misleading, however, insofar as it can be easily misunderstood for a system of propositions about the nature of reality, which is far from the case in this context. In Guénon’s words: “Knowledge belonging to the universal order of necessity lies beyond all the distinctions that condition the knowledge of individual things, of which that between subject and object is a general and basic type” (2001a, 75).

Metaphysics is thus inexpressible “with” language, for language always assumes the subject-object distinction, which is precisely what metaphysics, in this specific understanding, is said to overcome. However, it can be expressed “in-and-through” language, whereby the dynamics of language – its perpetual unfoldment, mutation, and self-transcendence – engenders the birth of the said distinction, its origin and source. We are dealing, then, not with a system of propositional knowledge, but rather with what Dōgen terms practice-realization (修證, shushō) (T2580), where these two aspects are inextricably linked: “When one speaks of the means of attaining metaphysical knowledge, it is evident that such means can only be one and the same thing as knowledge itself, in which subject and object are essentially unified; this amounts to saying that the means in question, if indeed it is permissible to describe it by that word, cannot in any way resemble the exercise of a discursive faculty such as individual human reason” (Guénon, 2001a, 75). Or, in the language of Zen, “not depending upon the letter, but pointing directly to one’s Mind” (Suzuki, 1938: 48).

Perennialists concur with eliminativists that, being ineffable, metaphysics can only be pointed at by statements, doctrines, and other means, all of which are by definition inadequate, but nevertheless necessary as a starting point, “an aid toward understanding that which in itself remains inexpressible” (Guénon, 2001a, 75). However, and this is where the two strands part ways, this pointing must not be understood as an arbitrary reference to a wholly separate realm – say, the realm of pristine experience – whereby the pointing would be completely severed from that which is pointed at. No: linguistic, cultural, and other aspects are no less characteristic of human experience as are, say, sensations or affects. Thus, in line with constructivists, perennialists argue that it is in-and-through the very act of pointing – through the seeming vagaries of different socio-cultural practices – that the Absolute actualizes itself. Where they disagree with constructivists, however, is in their belief that this Absolute cannot be exhausted by the peculiarities of any and all networks of pointings. The Absolute is not, and cannot, be exhausted, because these pointings themselves are caught up in the process of the unfoldment, and therefore never static or ultimate, but rather always, so to speak, pointing beyond themselves.

Taking this approach has three main advantages. First, it allows us to avoid the two extreme poles of modernist thought: demonization versus fetishization of language. Both focus on language as a static system of established meanings, and neither pay enough attention to the origins and modulations of those meanings. That is, instead of removing structures (eliminativism) or adding structures (constructivism), the most important aspect is the process of structuration itself – the birth of wholes, the manifestation of forms, in the vibrant framework of linguistic acts. Second, it gives us a new and fruitful understanding of the relationship between concrete doctrines and practices on the one hand, and their soteriological aim on the other. In a certain sense, one may say, as eliminativists do, that the end (the Absolute) is always already “here”, but is “overlaid” by language, culture, etc. However, this can only be properly understood if the particular “here” – the particular socio-cultural setting in which I am situated – is recognized, by myself, precisely as an aspect of the Absolute – as that which, in its unique way, allows one of its facets to manifest itself and thus can be said to symbolize the Absolute. Third, it makes intelligible the unity of a particular tradition (e.g., Zen in different cultural contexts), as well as the unity of different religious traditions (e.g., in Suzuki, 2002).[7]While perennialists do hold that all traditions are merely different paths leading to the same peak, a view that we agree with (see Vörös, 2013), all that is said here in the context of Zen still … Continue reading The latter two points will be elaborated in more detail in the next section.

5 Enlightenment symbolized

We have noted that, for perennialists, doctrines and practices symbolize enlightenment, i.e., the “order” of the Absolute. How are we to understand this? Since a detailed account of religious symbolism is beyond the scope of this article, we will, in what follows, focus on merely two aspects which are particularly important for our purposes. Both of these draw on the original meaning of the word “symbol”, namely: symbol as “that which throws or casts together” and symbol as a “token” or a “sign”. The crucial point is that what determines the symbol as a symbol is its capacity to bring together linguistic, practical, etc., means of a given socio-cultural context (a given “tradition”), but to do so in a way that allows for this context to meaningfully break through and reorganize itself. That is to say, a symbol is fundamentally a casting together of existing expressive means, whereby a new structure gets instantiated, in the light of which these expressive means acquire a completely novel orientation, dynamism, and significance. The birth of this new structure – the moment of its originary emergence – is a glimpse, however temporary or provisional, into one of the aspects of the Absolute (see e.g., Guénon, 2001d, 118ff.).

Two things are important here. On the one hand, because different traditions constitute different integrated wholes – with different expressive means available to them – symbols are, by necessity, concrete and particular (Schuon, 1984, 18). In their bringing together of the expressive means available in a given milieu, they need to be mindful of the expressive particularities of the milieu if they are to truly make sense (literally: constitute, or bring forth, a genuinely new domain of significance). The particularities of a certain symbolic expression are thus not contingent and redundant; they are, so to speak, the “flesh” of the symbol, its capacity to consume us and nourish our linguistic sensibilities.

On the other hand, while being firmly embedded into the framework of existing expressive means, symbols use these means in a way that allows them to fold back on, and thus break away from, themselves (ibid., 67). That is, they create a “crack” or a “hollow” in the fabric of a context – an “axis” around which meaningful structures can (re)order themselves. The symbol as a “sign” of the Absolute is thus both within and beyond language, it is, we might say, a temporary resting place of language in the process of its structuration. This is overlooked both by those who seek its meaning solely in that which is beyond it (eliminativists) and by those who seek its meaning solely in that which is within it (constructivists). The former overlook the “casting together” aspect of the symbol, the latter its function as a “sign” or a “token”.

This understanding of symbolism opens up an interesting middle way between eliminativism and constructivism. On the one hand, there is no question of reducing realization to the culturally and linguistically conditioned practices that lead to it; but, on the other, it is likewise impossible to speak of liberation apart from the specific tradition in which it is rooted. Esoterism and exoterism are inseparable: the former without the latter becomes a fruitless search for “end without means […], spirit without letter” (Smith, 1984, xxiv), while exoteric forms without an esoteric nucleus are reduced to nothing but “their most external elements, namely, literalism and sentimentality” (Schuon, 1984, 10).

Symbols, which constitute the exoteric part of a tradition, are thus neither causes nor reasons for enlightenment, or the esoteric parts of that self-same tradition. For if they were causes, then a mere exposure to a symbol or a mere detection of it (without any comprehension) would result in a specific state or reaction: if one studies this and does that, then enlightenment will follow (Vörös, 2019, 89). If, on the other hand, they were reasons, it should be possible to attain enlightenment through voluntary mental effort – in other words, we could simply reason ourselves into enlightenment. Instead, they can perhaps be best conceptualized as what in the phenomenological tradition is called motivation (Merleau-Ponty, 2002, 301).

Motives, unlike causes, act through their significance, i.e., they are not merely factual juxtapositions, but something that has to be apprehended. However, this significance, unlike the significance associated with reasons, is not a matter of clearly articulated ideas (explicit actualities), but a matter of tacit significances (implicit possibilities) (ibid.). There is, then, a meaningful (not arbitrary or mechanistic) relationship between the symbol and the symbolized, yet one that has to do not with explicit chains of reasoning, but rather with what we might call “existentially transformative gropings” (Vörös, 2019; 2021). In other words, symbols function as motives – as beckonings or solicitations – that invite us not to passively (automatically) react to what is given or to actively manipulate the already constituted meanings, but to transform our mode of being – our ordinary manner of existence – so as to be able to realize what a given symbol points to. In this sense, symbols are not so much prereflective or prerational, but rather what Guénon calls suprarational (Guénon, 2001a, 75), for they point above the structures of meaning and reasoning that are deemed meaningful within a given context.

It is this pre- or suprarational nature of motivation that provides us with an understanding of how Zen, with its decidedly non-scholarly and at times iconoclastic attitude, is no less a complete tradition and integral whole – a “spiritual organism” (Schuon, 1984, 108) – even if one completely eschews all study of scripture, as some more radical Zen teachers would doubtless recommend. Zen is not “universal mysticism”, a royal road to what we imagine to be “pure experience”, bereft of traditional context, because “symbolic” cannot be identified with “propositional” or “textual”. The seemingly humble ensō, the cosmic mudrā, the lotus position, the “turning word” of a kōan, or even the unexpected strike of a staff: these symbols point to liberation no less completely than the most diligent study of the Twelvefold Canon, for they “precede knowing and seeing”, as thinking and discrimination fall by the wayside (Dōgen, 2007b, 365). Nothing about these expedient means is arbitrary, and yet this isn’t to say that enlightenment is exclusive – let alone reducible – to a particular historical form: when the realm of discriminatory thinking, subject and object, is left behind for that which is wholly beyond expression, how could there be any talk of individuality?

6 Conclusion

In contemporary Western approaches to Zen, two radical views have become dominant: eliminativism, which understands enlightenment as the cutting off of a particular mental habit, accomplished by arbitrary means, and constructivism, which imprisons liberation into nothing more than the exercise of certain linguistic and cultural conventions. We have presented the key difficulties inherent in both views before trying to sketch out an alternative, drawing on the largely neglected work of perennialist thinkers and a phenomenologically informed notion of symbolism and motivation. By taking the idea of the symbol in its double meaning, namely as that which “casts together” the culturally conditioned particularities of Zen into a unified tradition, and yet points beyond them as a “sign” of something that itself transcends all description, we can do justice both to the crucial role played by concrete practices and to the transcendent nature of their soteriological end.

In this manner, we can avoid the pitfall of either severing the end from the means or reducing the former to the latter – where both hermeneutical transgressions serve only to fit Zen neatly into our own preconceived conceptual boxes. If we wish to take Zen (or perennialism) seriously, then we must acknowledge that anything like an exhaustive explanation of enlightenment is, and must remain, out of the question. At best, what we can approach is an understanding of what the act of pointing at enlightenment involves, while cautiously avoiding any tendency to mistake the explanation for what is explained, the (admittedly crude) map for the ineffable landscape, the conditioned for the ultimate. To return to the very beginning, “not speaking is how a buddha speaks”, and thus “if we want to attain the matter of the ineffable, we should practice the matter of the ineffable at once” (Dōgen, 2007b, 363).

References

Bodhidharma, The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma, San Francisco 1989.

van der Braak, A., Reimagining Zen in a Secular Age, Leiden 2020.

Coomaraswamy, A.K., Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism, New York 1916.

Coomaraswamy, A.K., A New Approach to the Vedas, London 1933.

Coomaraswamy, A.K., Hinduism and Buddhism, Mountain View CA 2011.

Dōgen, Shōbōgenzō, Mt. Shasta 2007a.

Dōgen, Shōbōgenzō: The True Dharma-Eye Treasury, Volume I, Berkeley 2007b.

Ford, J.I., Zen master who? A guide to the people and stories of Zen, Boston 2006.

Fromm, E. et al., Zen-Buddhismus und Psychoanalyse, Frankfurt am Main 1971.

Guénon, R., Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines, Hillsdale, New York 2001a.

Guénon, R., Man and His Becoming According to the Vedanta, Hillsdale, New York 2001b.

Guénon, R., The Multiple States of the Being, Hillsdale, New York 2001c.

Guénon, R., The Symbolism of the Cross, Hillsdale, New York 2001d.

Harrington, A. et al., Mindfulness meditation: Frames and choices, American Psychologist, 2013, pp. 1–27.

Merleau-Ponty, M., Phenomenology of Perception, London & New York 2002.

Nasr, S.H., Knowledge and the Sacred, New York 1989.

Red Pine, The Lankavatara Sutra: Translation and Commentary, Berkeley 2012.

Schuon, F., Language of the Self, Madras 1959.

Schuon, F., The Transcendent Unity of Religions, Wheaton 1984.

Schuon, F., Treasures of Buddhism, Bloomington 2018.

Smith, H., Introduction to the Revised Edition, in: Schuon, F., The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Wheaton 1984, pp. ix–xxxviii.

Suzuki, D.T., Zen Buddhism, Monumenta Nipponica 1 (1), 1938, pp. 48–57.

Suzuki, D.T., Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist, London & New York 2002.

Taylor, E., Shadow Culture: Psychology and Spirituality in America, Berkeley 2000.

Vörös, S., Podobe neupodobljivega: (nevro)znanost, fenomenologija, mistika, Ljubljana 2013.

Vörös, S., Embodying the Non-Dual: A Phenomenological Perspective on Shikantaza, Journal of Consciousness Studies 26 (7–8), 2019, pp. 70–94.

Vörös, S., All Is Burning: Buddhist Mindfulness as Radical Reflection, Religions 12, 1092, 2021.

Wallace, B. A. (ed.), Buddhism and Science: Breaking new ground, New York 2003.

Wright, D., Rethinking Transcendence: The Role of Language in Zen Experience, Philosophy East and West 42 (1), 1992, pp. 113–138.

About the Authors

Adnan Sivić is a Young Researcher at the Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, where he is currently working on his Ph.D. thesis under the supervision of Dr. Sebastjan Vörös. His primary research interests include phenomenology, the philosophy of religion, Buddhist philosophy, perennialism, and enactivism.

Sebastjan Vörös, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. His research interests span philosophy and history of science, epistemology, and Buddhist and Christian philosophy. He is the author of Podobe neupodobljivega (The Images of the Unimaginable), in which he addresses mystical experiences from neuroscientific, phenomenological, and epistemological perspectives, and several articles on enactivism, embodiment, and (neuro)phenomenology. He is currently writing a book on the life and work of Francisco Varela.

References

| ↑1 | Co-first authorship statement: both authors contributed equally to this work. The paper is a result of the work within the research program “Philosophical Investigations” (P6-0252), financed by ARRS, the Slovenian Research Agency. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | We will be referencing Red Pine’s translation of the Laṅkāvatārasūtra throughout; a reference to Guṇabhadra’s Chinese text from the Taishō Tripiṭaka will also be given, but the volume and text numbers will be omitted in all further occurrences. |

| ↑3 | See Vörös, 2013, 23–102. |

| ↑4 | While Dōgen’s Sōtō school does differ from other Zen traditions in its concrete forms of practice (although the difference is primarily one of emphasis), we can still take it as representative with regard to its understanding of language and enlightenment (Vörös, 2013, 446–461). |

| ↑5 | Note that this denial applies especially to the destruction of mental faculties or “views” (見). In a different section of the Laṅkāvatāra, the view that nirvāṇa consists in the destruction of hindrances is criticized in more depth and explicitly identified with a type of nihilism (499a11–b21; Pine, 2012, 177–179). |

| ↑6 | This term is used very often in perennialist texts, but it doesn’t entail any sort of objectivization of metaphysical realization. What is in question here is beyond what can properly be subsumed under Being, let alone any narrower determination (Guénon, 2001d, 10; 2001c). |

| ↑7 | While perennialists do hold that all traditions are merely different paths leading to the same peak, a view that we agree with (see Vörös, 2013), all that is said here in the context of Zen still holds even if one rejects this assumption. |