Epoché (XVI), 4. 3. 2021

A synopsis of our reading of The Normal and the Pathological by Georges Canguilhem

Part II/Ch. 3 “Norm and Average” (pp. 151-179)

Abridgment by: Sebastjan Vörös

[his outline and commentary of the whole book can be found here]

Chapter III: Norm and Average

The modern physiologist tends to revert to the concept of “average” when looking for an objective and scientifically valid equivalent of the concept of normal or norm. Bichat and Bernard, for instance, were still quite skeptical of investigations revolving around such “averages”. See for instance Bichat’s comment:

“Urine, saliva, bile, etc., taken at random from this or that subject

are analyzed and from their examination animal chemistry is born, whatever it may be. But this is not physiological chemistry; if I may say so, it is the cadaverous anatomy of fluids. Their physiology consists in the knowledge of innumerable variations undergone by the fluids as they follow the state of their respective organs.” (151)

Similar skepticism echoes in the following Bernard’s rule:

“In physiology average descriptions of experiments must never be given because the real relations of phenomena disappear in this average; when dealing with complex and variable experiments, we must study their different circumstances and then offer the most perfect experiment as type, which will always represent a true fact.” (152)

Research on average biological values has no meaning as far as the same individual is concerned.

Example: the analysis of “average urine” over a day (24 hrs) is “the analysis of urine which does not exist”, since the urine from the fasting state differs from that of digestion.

I add the following quote for the giggles:

“The culmination [of this kind of experiment] was conceived by a physiologist who took urine from the urinal at the train station through which passed people of all nations, and believe he could thus produce the analysis of average European urine.”

In general, for Bernard, “the normal” was construed as an ideal type in determined experimental conditions and not as an arithmetic average or statistical frequency (152).

Pierre Vendryes tried to alter this conception and bring in the statistical interpretation. According to him, the variations undergone by physiological constants (e.g., glycemia) are divergences from an average, but an individual average. The terms “divergence” and “average” here have a probabilistic meaning (153).

However, C. thinks that Vendryes’ approach is not, and cannot be, purely statistical. For instance, when Bernard emphasized that the most perfect experiment serves as a type, i.e., a norm, for comparison, he openly admitted that the physiologist brings to bear the norm of his own choosing in the physiology experiment and that he does not withdraw it. And it would seem, claims C. that Vendryes must proceed in the same way. To begin with, [i] which conditions do you characterize as normals? Further, [ii] how do you know that the individual whose constants you are about to study represents the human type? If you are to proceed statistically, you will have to compare his measures with the measures of statistical averages in individuals placed in conditions as similar as possible. But then – within what range of oscillations around a purely theoretical average value are individuals to be deemed normal? (153-4)

Here, C. reverst to the work of A. Mayer and H. Leugier who, according to him, have dealt with this issue with “great clarity and honesty”.

(a) Mayer first enumerates all the elements of contemporary physiological biometry (temperature, basal metabolism, blood gases, etc.), and then goes on to say that, in order to represent a species, we have chosen norms which are in fat constants determined by averages: the normal living being is a living being who conforms to these norms. But what of those individuals who diverge from the average? In Mayer’s views, such divergences are ubiquitous, and in-depth investigations are needed to establish which divergences are compatible with extended survival (154).

(b) Laguier shows why such a study is difficult with regards to human beings. He does this by expounding on Quetelet’s theory of the average man.

Example: height: Even if you acquire a curve for the distribution of height, you still need guiding hypotheses and practical conventions to determine what value for heights (toward the tall or the short) constitutes the transition from normal to abnormal (154-5)

In general: “statistics offer no means for deciding whether a divergence is normal or abnormal” (155)

Now, couldn’t we use the following as a universal convention: normal = the individual whose biometrical value allows one to predict that his lifespan, barring an accident, will be appropriate to the lifespan of his species. However, the same problem emerges: people who die of old age (senescence) have very different life spans – what value do we therefore take: the average, the maximum, etc.? Further, this normality would not exclude other abnormalities: a certain congenital deformity, say, can be compatible with a very long life. (155)

In general:

“if average state of the characteristic studied in the observed group can furnish a substitute for objectivity in the determination of partial normality, the nature of the section about the average remains arbitrary; in any case all objectivity vanishes in the determination of a universal normality.” (155)

For this reason C. asks:

“Is it still more modest or, on the other hand, more ambitious to assert the logical independence of the concepts of norm and average and consequently the definitive impossibility of producing the full equivalent of the anatomical or physiological normal in the form of an objectively calculated average?” (155-6)

In light of this C. tries to summarize the meaning and scope of biometric research in physiology. In general, the physiologist is well aware that, for him, “norm” and “average” are two inseparable concepts. But how should we understand this inseparability?

(a) Average → norm: The usual way is to try to subsume norm under average, since the latter seems to be directly capable of objective definition. However, the difficulties in this approach are, as we have seen, insurmountable.

(b) Norm → average: C. proposes a different approach, i.e., that we should subordinate average to the norm (and not vice versa) (156).

At this point, C. undertakes a brief survey of the development of the biometric approach.

(a) Adolphe Quetelet: Quetelet performed systematic studies on human height, establishing that individual variations (fluctuations) in height can be expressed in terms of laws of chance (calculation of probabilities) (156). For him, this had profound metaphysical implications, as it seemed to him to be an indication that there exists “a type or module” for the human race “whose different proportions could be easily determined”. Thus, from any large number of men whose height varies between determined limits, those who come closest to the average height are the most numerous, those who diverge from it the most are the least numerous. Quetelet called this human type the “average man” (157). Note that the typical average is completely different from the arithmetical average: if we decide to measure the height of several houses we may get an average height (= arithmetical average), but such that no house can be found whose own height approaches the average (the average, in this case, is a mere statistical mean). In human beings, this is not the case: there is such an entity as an “average man”, and for this reason, Quetelet argued, the existence of a (typical) averageimplies the existence of a regularity, which needs to be interpreted in an explicitly ontological sense (form him it was a sign that man is subject to divine laws) (157-8).

Quetelet’s conception is most interesting because of its identification of “true average” on the one hand and “statistical frequency” and “norm” on the other. In general, what needs to be pointed out here, is (1) that Quetelet distinguishes two kinds of averages, i.e. (i) arithmetical average (median) and true (typical) average, and (2) that instead of presenting the average as the empirical foundation of the norm he explicitly presents an ontological regularity which expresses itself in the average (158).

(a) Maurice Halbwachs: Halbwachs argues that Quetelet is mistaken and that the distribution of human heights around an average is not a phenomenon to which the laws of chance can be applied (158). The first condition for such application is namely that phenomena are realizations which are completely independent of one another, so that no one of them exerts any influence on the one that follows. This, however, does not hold true in the case of constant organic effects. For this would presuppose that, say, (i) physical facts resulting from the environment and (ii) physiological facts related to the process of growth are independent, which is untenable from the human perspective, where social norms (cf. i) interfere with biological laws (cf. ii): “In short, heredity and tradition, habit and custom, are as much forms of dependence and interindividual connection as they are obstacles to an adequate utilization of the calculation of probabilities.” (158)

Example: height (Quetelet’s most favourite object of study): height would be a purely biological fact if it were studied in a set of individuals constituting a “pure line” (either animal or plant), for in this case, the fluctuations would derive exclusively from the action of the environment; yet in the human species, height is a phenomenon that is inseparably biological and social; for even if height is a function of the environment, the latter must be understood as the geographical environment; but since man is a geographical agent, geography is thoroughly penetrated by history (in the form of collective technologies); e.g., statistical studies have demonstrated the impact of the dragining of the Sologne marshes or the improved diet on the height of the inhabitants.

However, C. doesn’t think that a swing in the direction of (radical?) social determination is the right way to proceed:

“But we believe that if Quetelet made a mistake in attributing a value of a divine norm to the average of a human anatomical characteristic, this lies perhaps only in specifying the norm, not in interpreting the average as a sign of a norm. If it is true that the human body is in one sense a product of social activity, it is not absurd to assume that the constancy of certain traits, revealed by an average, depends on the conscious or unconscious fidelity to certain norms of life. Consequently, in the human species, statistical frequency expresses not only vital but also social normativity. A human trait would not be normal because frequent but frequent because normal, that is, normative in one given kind of life, taking these words kind of life in the sense given them by the geographers of the school of Vidal de la Blache [founder of French “human geography”]’” (159-60)

This is even clearer if, instead of an anatomical feature, we focus on a physiological one, e.g. [example] longevity. Jean Pierre Flourens, for instance, linked the lifespan to the specific duration of growth; the latter, in turn, he defined in terms of the union of bones at their epiphyses: “Man grows for twenty years and lives for five times twenty, that is, 100 years.” Flourens is, of course, well aware that this number is neither frequent nor the average duration, but he feels that it is a number of years that could be reached more often if disturbing causes (disease, accidents, etc.) did not get in the way (similar ideas were held by Élie Metchnikoff) (160-1).

But here, a similar issue emerges. Namely, when we speak of an average life in order to show that it is growing gradually, we associate it with the action that man, taken collectively, exercises on himself and his surroundings. This is the reason why Halbwachs talks of death as a social phenomenon, arguing that the age of death is determined largely by working and hygienic conditions, attention paid to fatigue and diseases, etc. He goes on to say – interestingly, I think – that everything happens as if a society had “the mortality that suits it”, the number of the dead and their distribution into different age groups expressing the importance which the society does (not) give to the protraction of life. The average lifespan, then, is not the biologically normal, but ina sense, the socially normative lifespan. Again, the norm is not deduced from, but rather expressed in the average (161).

One possible objection to this would be that, even if this is true for superficial human characteristics for which there does exist a margin of tolerance where social differences are in evidence, it is not true for either (i) fundamental human characteristics (e.g., glycemia, calcemia, blood pH) or – generally speaking – (ii) strictly specific characteristics in animals (161-2).

C. responds that it is decidedly not his intention to maintain that anatomic-physiologic averages express social norms and values in animals; what he does ask is whether they wouldn’t express vital norms and values.

Example: butterfly species (Tessier; see above):

“[A] very different meaning could be given to the existence of an average of the most frequent characteristics than that attributed to it by Quetelet. It would not express a specific stable equilibrium but rather the unstable equilibrium of nearly equal norms and forms of life temporarily brought together. Instead of considering a specific type as being really stable because it presents characteristics devoid of any incompatibility, it could be considered as being apparently stable because it has temporarily succeeded in reconciling opposing demands by means of a set of compensations. A normal specific form would be the product of a normalization between functions and organs whose synthetic harmony is obtained in defined conditions and is not given.” (162) [!!!] [vitalism]

C. points out that, with regards to man and his permanent physiological characteristics, only a comparative human physiology and pathology could provide a precise answer to his hypotheses, and that such an enterprise is still lacking. The gap has been, in his opinion, partly filled by the French geographer Max Sorre, whose work he intends to examine more closely later in the text (163).

C. focuses on some of the potential problems in the biometric research into human physiological constants. To begin with, one of the difficulties in determining physiological constants by establishing averages obtained experimentally in a laboratory setting is that we run the risk of presenting normal man as a mediocre man. It could be replied that the laboratory conditions have greatly improved since the times of Bernard, and that the modern physiologist looks to the concrete man and not to the laboratory subject in a very artificial situation, and that he himself invests the tolerated margins of variations with biometrical values. In this regard,Tibaudet’s witty remarks proves to hit the nail on its head:

“It is the record figures, not physiology that answers the question: how many meters can a man jump?” (164)

C. concludes:

“In short, physiology would be only one sure and precise method for recording and standardizing the functional freedoms acquired or rather progressively mastered by man. If we can speak of normal man as determined by the physiologist, it is because normative men exist for whom it is normal to break norms and establish new ones.” (164-5)

As expressions of human biological normativity one finds interesting not only individual variations of the so-called civilized white man’s common physiological “themes”, but even more so the variations of the themes from group to group, depending on the collective norms of life.

Example: Hindu yogis: mastery over their vegetative functions (Charles Laubry, Thér`ese Brosse) (165); such accomplishments definitely amount to the breaking of physiological norms, unless one chooses, unconvincingly, to consider such results pathological. C. quotes Laurby and Brosse in this regards:

“If yogis are ignorant of the structure of their organs, they are indisputable masters of their functions. They enjoy a magnificent state of health and yet they have inflicted on themselves years of exercises which they couldn’t have stood if they hadn’t respected the laws of physiological activity. […] The will seems to act as a pharmacodynamic

test and for our superior faculties we glimpse an infinite power of regulation and order.” (166)

In light of this Brosse puts forward the following remarks regarding pathology:

“The problem of functional pathology, considered from the perspective of conscious activity related to the psychophysiological levels it uses, seems intimately connected with that of education. As the consequence of a sensory, active, emotional education, badly done or not done, it urgently calls for a reeducation. More and more the idea of health or normality ceases to appear as that of conformity to an outer idea (athlete in body, bachelier [lycée graduate] in mind). It takes its place in the relation between the conscious I and its psychophysiological organisms; it is relativist and individualist.” (166)

In what follows C. goes through some studies in the field of physiology and comparative physiology (e.g., studies by Borak [cf. 166-9] showing the relationship between types of existence and the curves of diuresis and temperature (slow rhythms), pulse and respiration (fast rhythms); by Labbé on the etiology of nutritional diseases [cf. 169], by Sorre on the relationship between pathophysiology and climates, diets and biological environment [169-71]). C. concludes:

“We can only conclude that to consider the education of functions

as a therapeutic measure […] is to admit that functional constants are habitual norms. What habit has made, habit unmakes and remakes. If diseases can be defined as defects in terms other than metaphorical, then physiological constants must be definable, other than metaphorically, as virtues in the old sense of the word, which blends virtue, power and function.” (169)

And further, in relation to Sorre’s studies:

“Constants are presented with an average frequency and value in a given group which gives them the value of normal and this normal is truly the expression of a normativity. The physiological constant is the expression of a physiological optimum in given conditions among which we must bear in mind those which the living being in general, and homo faber in particular, give themselves.” (171)

Example: hypoglycemia in African blacks: in a study by Pales and Monglond, 66% of Brazzavile natives (n = 84) were hypoglycemic (27% of them severely so); yet these natives seemed to be able to withhold hypoglycemias which would be considered grave if not mortal to a European; the causes for this would have to be sought in chronic undernourishment, chronic and polymorphous intenstinal parasitism and malaria; in C.’s view, if the European can serve as a norm, it is only to the extent that his kind of life will be able to pass as normative; but this is dubious, so one might conclude that the black has physiological means in accordance with the life he leads (171-2).

The relativity of certain aspects of anatomic and physiological norms and consequently of certain pathological disturbances is also present in the field of paleopathology (i.e., comparative study of pathology in present and earlier groups). Again C. draws on several studies (by Pales, Moodie, Vallois, etc.; 172-3). The conclusion he draws from this is the following:

“[T]he differences of cosmic milieu, technical equipment and way of life […] make the abnormal of today the normal of yesterday.” (174)

Possible objection: C. points out that one may question the conclusions of such studies with regards to the physiological significance of functional constants interpreted as habitual norms of life.

C’s answer: Note that these norms are not the product of individual habits, i.e., habits which a certain individual could take over or leave aside as he pleased. If we admit man’s functional plasticity, linked in him to vital normativity, this does not translate into a total, instantaneous or a purely individual malleability: “What the species has worked out over the course of millennia does not change in a matter of days.” (174)

C. in general concurs with Kayser who says the following:

“It seems a proven fact that with man the climatic factor has no direct effect on metabolism; it is only in a very progressive manner that climate, by modifying the mode of life and allowing the consolidation of special races, has any lasting action on basal metabolism.” (175)

In broader terms, C.’s position could be stated as follows:

“In short, to consider the average values of human physiological constants as the expression of vital collective norms would only amount to saying that the human race, in inventing kinds of life, invents physiological behaviors at the same time.” (175)

However, one might object: are the kinds of life not imposed on us?

“Environments offer man only potentialities for technical utilization and collective activity. Choice decides. Let us be clear that it is not a question of an explicit and conscious choice. But from the moment several collective norms of life are possible in a given milieu, the one adopted, whose antiquity makes it seem natural, is, in the final analysis, the one chosen.” (175)

There are cases, however, where it is possible do demonstrate the influence of explicit choice on the direction of some physiological behaviour.

Example: pigeon’s circadian rhythm (Kayser): the day and night variations in the central temperature are an example of a vegetative phenomenon that is subordinated to relational functions, i.e., the phenomenon is not determined by isolated mechanisms, but is the expression of a variation in attitude of the entire organism with respect to the environment (the adaptation of the organism to the day-light cycles) (175-6).

Example: circadian rhythm in man (Mosso, Benedict, Toulouse, Piéron): here, too, one sees how the rhythm (physiological constant) changesin relation to the conditions of activity, i.e., in relation to a collective and even individual kind of life.

Admittedly, it is not certain to what extent other physiological constants would appear as the effect of a supple adaption of human behaviour. But the crucial point is to show that this is an important question (177).

Summary: According to C, the concepts of “norm” and “average” must be considered as two different concepts. Instead of searching for an objective definition of the normal, physiology would do better to recognize the original normative character of life. Its true role would then consist in determining exactly the content of the norms to which life has succeeded in fixing itself without prejudicing the (im)possibility of eventually correcting these norms (177-8).

Interesting conclusion of the chapter:

“Bichat said that animals inhabit the world while plants belong only to their place of origin. This idea is even more true of men than of animals. Man has succeeded in living in all climates; he is [i] the only animal – with the possible exception of spiders – whose area of expansion equals the area of the earth. But above all he is [ii] the animal who, through technology, succeeds in varying even the ambience of his activity on the spot, thereby showing himself now as the only species capable of variation. Is it absurd to assume that in the long run man’s natural organs can express the influence of the artificial organs through which he has multiplied and still multiplies the power of the first? We are aware that the heredity of acquired characteristics seems to most biologists to be a problem which has been resolved in the negative. We take the liberty of asking ourselves whether the theory of the environment’s action on the living being were not on the verge of recovering from long discredit. True, it could be objected that in this case biological constants would express the effect of external conditions of existence on the living being and that our suppositions concerning the normative value of [natural] constants would be deprived of meaning. They would certainly be so if variable biological characteristics expressed change of environment, as variations in acceleration due to weight are related to latitude. But we repeat that biological functions are unintelligible as observation reveals them to us, if they express only states of a material which is passive before changes in the environment. In fact the environment of the living being is also the work of the living being who chooses to shield himself from or submit himself to certain influences. We can say of the universe of every living thing what Reininger says of the universe of man: “Unser Weltbild ist immer zugleich ein Wertbild”, our image of the world is always a display of values as well.” (178-9) [!!!]

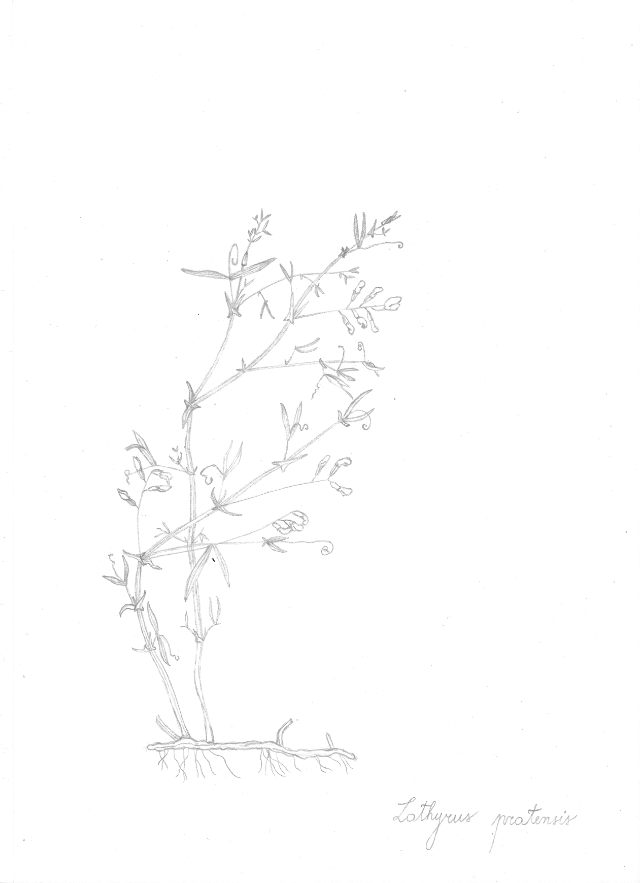

meadow vetchling, Lathyrus pratensis (sl. travniški grahor)

Discussion

Part 1

4. 3. 2020

Presenter: Izak Hudnik

Part 2

11. 3. 2020

Presenter: Sebastjan Vörös